MALCOLM KIRK

PHOTOGRAPHS

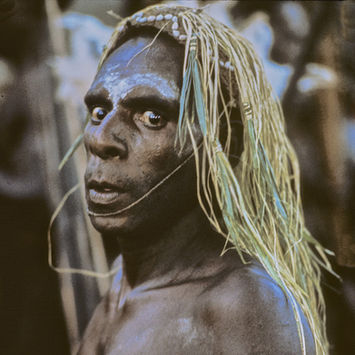

NEW GUINEA/ASMAT

In 1970, sponsored once again by National Geographic, I flew into the Asmat region on the south coast of West Papua – a flat expanse of sweltering jungle and mangrove swamp intersected by numerous rivers that originate in the central mountains and coil their way out to the Arafura Sea. Mud permeates the forest floor and extends thigh-deep for a considerable distance beyond the shoreline at low tide.

The Asmat people occupy small settlements strung out along the riverbanks, their huts elevated on wooden stilts to protect them from flooding and potential attack. Their headhunting tradition is linked to an affinity with the sago tree – their primary food source – and to its perceived resemblance to the human body. The legs correspond to the tree's roots, the torso to its trunk, and the arms to its branches, while the head is analogous to the germinating fruit, symbolising the continuity of life. Each village has its ceremonial bachelors’ house, or jeu, where seated boys periodically undergo initiation into manhood, clasping freshly severed heads between their thighs in their transition to sexual maturity. After undergoing a ritual death and rebirth by submersion in the ocean, they subsequently assume the names and physical attributes of the victims and are even recognized as reincarnations of those individuals by the victims’ own relatives.

The cycle continues unabated when the kin of those killed seek revenge upon the attackers. Tall wood bisj poles – carved with representations of relatives whose deaths must be avenged – are mounted outside the jeu prior to the departure of the raiding party. Following the boys’ initiation, the skulls are flayed and used as pillows to ward off the vengeful spirits of the dead when they emerge at night. Cannibalism constitutes a subsidiary aspect of the headhunting ritual, with body parts distributed among members and relatives of the successful raiding party. Lower jaws are detached from the heads and worn on the killers’ chests as symbols of prowess, while leg bones are fashioned into daggers incised with emblematic designs.

I spent over three months among the Asmat, together with two companions, travelling from village to village in a canoe outfitted with an outboard motor. In the remote headwaters of one river, we came across a headhunting party intent on attacking a settlement farther upstream. I stopped to photograph them until our local guide nervously pointed out that we were in imminent danger ourselves, so we made a hurried departure and continued farther upstream to warn the people there of an impending assault. On our return downstream, the raiders paddled toward us in their canoes in an attempt to cut us off, but we managed to speed past them to safety.

On another occasion, I witnessed an elaborate adoption ceremony intended to forge a bond between two rival villages. During the ritual, six adults – three men and three women – from one village underwent a symbolic birth before being adopted by members of the other. Each was decorated with strips of palm leaves and the three women were presented with bamboo food tongs, signifying their future obligation to feed their new parents once they came of age. They also wore symbolic umbilical cords fastened to stone axe heads around their waists.

All the men in the adopting village lay side by side, face down, on the floor of a hut, while the women stood astride them to form a tunnel representing the birth canal. Each infant then crawled through the canal over the men’s backs, and upon emerging at the other end was hidden beneath a pile of fronds – the placenta – by two elderly women acting as midwives. The midwives then parted the bundle to reveal the newborn infants within and, after opening their eyes, proceeded to sever the umbilical cords with slivers of sharp shell.

The six infants, now transformed into children, were then escorted outdoors, where the men were given toy bows and arrows to practice with. Later, they were paddled out to sea in the canoes of their adoptive parents, and on the return journey were taught the names of the trees and animals they passed along the route. By the time they arrived back in their new home, they had matured into adult members of the community.

I also investigated the fate of Michael Rockefeller, who disappeared here in 1961 during an expedition to collect Asmat woodcarvings. His father, Nelson Rockefeller, then Governor of New York State, organized a major search party, but no trace of him was ever found. I spoke with a Canadian missionary who was there at the time. Reluctant to talk openly, he requested that I turn off my tape recorder before confiding that the locals had told him Michael was killed by men from Otsjanep village, in payback for the shooting of five of their members by a Dutch patrol officer three years earlier. Two other Dutch missionaries – one of whom had organized the Rockefeller search party – confirmed what he had said. I twice visited Otsjanep myself hoping to uncover additional evidence, only to meet with a hostile reception on both occasions.